News

Harvard Alumni Email Forwarding Services to Remain Unchanged Despite Student Protest

News

Democracy Center to Close, Leaving Progressive Cambridge Groups Scrambling

News

Harvard Student Government Approves PSC Petition for Referendum on Israel Divestment

News

Cambridge City Manager Yi-An Huang ’05 Elected Co-Chair of Metropolitan Mayors Coalition

News

Cambridge Residents Slam Council Proposal to Delay Bike Lane Construction

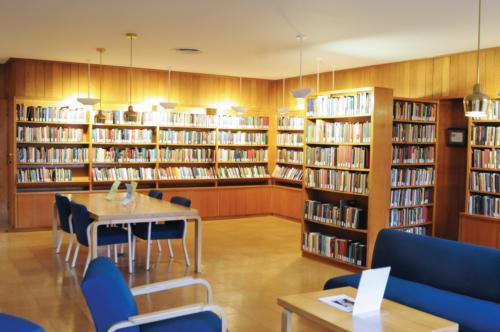

Woodberry Room Celebrates Poetic History

“Out of the ash I rise with my red hair, and I eat men like air.” Sylvia Plath’s strong voice projects from a black rectangular machine resting on a table. A dozen people sit in surrounding blue chairs, listening attentively. Some hold anthologies of Sylvia Plath’s poetry and follow along with the poet’s recorded voice. Others merely listen. On Friday afternoons in the George Edward Woodberry Poetry Room in Lamont Library, visitors gather to appreciate the recordings of prominent poets as part of REEL TIME, one of the new programs recently installed under the direction of new curator Christina S. Davis.

Since Davis arrived at Harvard in October, she has made efforts to share the famous, albeit a bit dusty, audio archives to which the Poetry Room lays claim. Boasting the voices of John Ashbery, Robert Frost, Vladimir Nabokov, and Ezra Pound, the Harvard collection of audio recordings is one of the most extensive in the nation. Through Davis’ new programs, the collection has become more accessible not only to the Harvard community but to the public as well.

“I wanted poetry to have its majesty but also to have personable, intimate forums,” Davis says.

During the past seven months, Davis has implemented three daytime programs in the Poetry Room. In addition to REEL TIME, a weekly listening hour that features audio recordings of poetry from the 20th and 21st centuries, there is IMPROMPTU POETICS, which invites guest poets to recording sessions in the Poetry Room, which are also open to the public. Lastly, Woodberry Works-in-Progress allows scholars and artists to speak with attendees about projects that are in their nascent stages.

“Seeing someone immersed in the outset of an idea, when the yesses and nos remain unsplit in it, humanizes it and allows us admittance,” Davis says about Works-in-Progress. She hopes that by having the opportunity to give feedback to these artists, students will feel as if they have influenced the works presented. Past projects discussed at Works-in-Progress include found poetry and the creation of the largest onsound poetry archive.

These programs have received praise from the Harvard community. Professor Peter M. Sacks, who teaches 20th-Century American Poetry, says the events have given his students the opportunity to immerse themselves in poetry through the real voices of their authors.

“There’s a welcoming range of taste, of emotion, of spirit,” Sacks says of the Poetry Room programs. “A genuine feeling of enterprise, of both adventure and devotion. There’s a living connection between the archive and the as-yet-unrecorded.”

On May 8, another program will be introduced to the Poetry Room. The Oral History Initiative is intended to allow visitors to be exposed to the nonacademic aspects of the poets they study. The first episode, “Three Friends of Robert Lowell,” will offer friends of the writer a chance to share personal anecdotes about him.

According to Davis, the events at the Poetry Room have attracted diverse crowds. Spanning class years, generations, concentrations, and involvement in the Harvard community, attendees of the programs vary in their experience with, and exposure to, poetry.

Davis says that the various individuals who visit the Poetry Room often strike up friendships after attending events. “Poetry is an inherently synthesizing art form,” she says.

In addition to being a social catalyst, poetry, according to Davis, is especially important in a university setting where students are taught specific methods of thinking.

“Poetry is a permanent place for questions to reside, free of all the answers we receive,” she says. “It is a mode of thought that allows us to become reunited with a more essential way of thinking.”

—Staff writer Anita B. Hofschneider can be reached at hofschn@fas.harvard.edu.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.